A few months ago a friend of mine lent me a mandolin.

I had been meaning to try my hand at the instrument for a while now, and even bought an old silvertone for cheap which, while pretty, showed up with an action so high it was almost unplayabale. So predictably, I didn't stick with it and it's now gathering dust alongside the couch.1

My friend's is only slightly less pretty, and most importantly, it plays like butter and stays in tune pretty well, so this time I've been much more diligent.

Since it wasn't that long ago, I remember the process I went through during the first few hours I spent with it, which got me to improvise simple things after less than a day's work, and I thought it could be interesting to describe it here.

I'm not trying to show off or even pretend I'm halfway competent yet. Honestly, I still suck at it. My intention is merely to demonstrate how applying a few basic harmonic concepts can speed you up when getting to know a new instrument.

Also, keep in mind that even though I was new to this instrument, I've been playing guitar for more than twenty years, which obviously helps tremendously with the mechanics. I've also had almost as long to internalize the theory I'll mention below. It took me a while to understand and memorize those concepts, and even longer to learn to hear them. My hope here is merely to show you how useful knowing that stuff can be.

So I've learned the major scale, now what ?

On the few occasions I had had to fool around with a mandolin before, I had deciphered and memorized the G major scale.

Learning a scale is an important step, but once you're done memorizing the pattern, it's not obvious what to do with it beyond running it up and down, which stops being fun after about two minutes. Figuring out how to turn that scale into music takes a while, and experimenting is not that easy if you have no idea where to start.

So my first impulse was to spot my arpeggios2. I started with the one chord (ie G Major) and stuck to the lower two strings to get started.

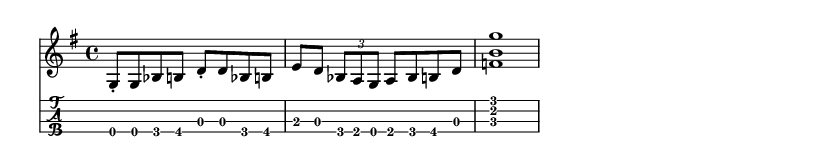

Without delving too deep into theory, the way to find those is to simply count the notes as you play your scale, and isolate the first, third and fifth notes from the pattern. Once you found those, keep running the scale until you hit the root again (in this case, G) and add that note to the three you just singled out to round things up:

As a guitar player, finding the major third was a no brainer. Frets work the same way, so I didn't have to think to know it lied 4 frets (2 whole steps) up from the root (here, the open G string). Having the fifth on the next open string didn't feel so natural3, though, so I spent a few minutes playing the arpeggio up and down, alternating with the full scale for reference.

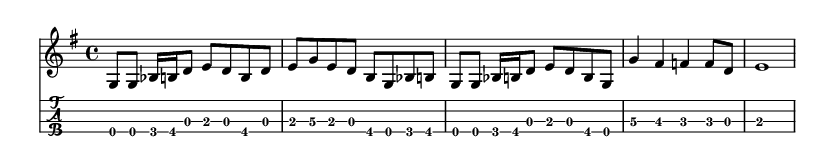

Once I got it under my fingers, I could play simple lines like this:

I'm fancying it up slightly with hammer-ons and pull-offs, but really all I'm doing is emphasizing the notes from the argeggio, using notes from the scale as passing tones and reaching for the root when I want things to resolve.

Bluesin it up

As a bluegrasser, I immediately wanted to dirty things up. Luckily, I already knew how to do just that.

Since I had already located my major third4, I only had to lower it by one half-step to switch to minor and get that sweet, bluesy feel. Resolve it back up to the regular third or down to the second, and I'm good to go.

In the same vein, lowering the root note by one full step will land me on the minor seventh. A nice trick is to get there chromatically, which tends to sound pretty cool. Check it out:

Switching chords

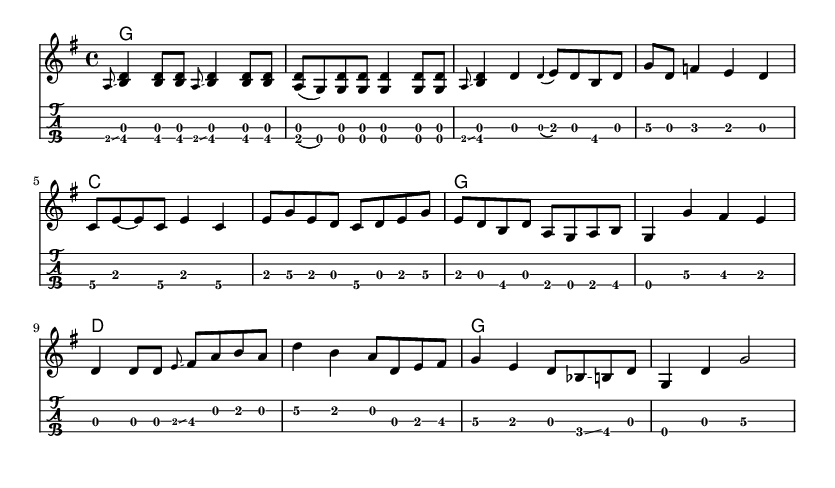

So, now that I'm on the seventh, my ear really wants to go to the IV chord (C in this case). I also know from experience that going down one more half step will yield the third of that new chord (you can hear me hang on it in the last exemple).5

But what then ? I have no idea where the C chord tones are on this new neck.

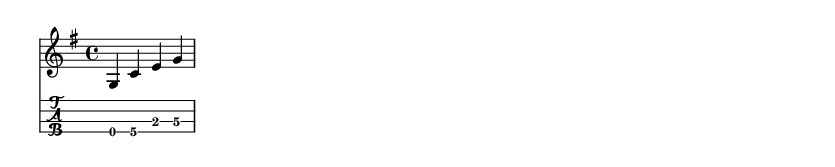

So I just stopped, went back to the full scale and took the time to spell it out, as I did for the G chord. which gave me this new pattern:

Again, I played it slowly a few times over, making mental notes on where the new root was6, and also the third in case I want to mess with it as I did on the G. And then I went back to fooling around.

Apart from my lousy timing, you might notice that I went ahead and played over the D chord as well. Since I had already spotted the scale's fifth note and noticed it was an open string, I simply moved the G arppeggio up one string and played around that. It could have gotten me into trouble had I tried to add more notes to it, but sticking to the chord tones was pretty safe (I still added a sixth in there because sixth are sweet).

So am I a mandolinist yet ?

Hell no. Far from it.

I've kept with the process I just described and included the two missing strings, and I can fake my way for a few bars on simple 3 chord songs, as long as they're in the key of G or D. If the song doesn't stick to a I IV V harmony, then I might get by if it's still diatonic, but forget about outlining the progression.

And that's about it.

The C arpeggio is still giving me trouble, as its shape is different enough from what I'm used to to trip me up. I've looked at closed position scales, and while I "get it" on a surface level, they feel foreign and I get lost at the first chord change.

There's still a long way to go, is what I'm getting at.

But it's nice to know what I don't know. It'll take a while before I actually know what I'm doing, but with the help of those basic harmonic notions, I can at least pinpoint what I need to work on.7

If all that number talk sounded like giberrish to you, sorry. If you learn how to build chords from the major scale, then it should all start to make sense. Juggling with those numbers and getting used to thinking with them takes some practice, but it's one of the first things you'll tackle if you ever decide to study harmony.

This is of course not the only or even right way to go about it, but it's mine. Some people are able to figure that stuff out entirely by ear. Not me, though. I needed to be able to put a name on things before I could make sense of them.

I barely use anything more advanced in my day to day, so hopefully I've shown how far a little understanding can get you.

Time to get rhythm

As I said, I went through that process a couple months ago, and I haven't delved much further as far as melody goes.

I switched my attention to chords and playing backup. Being able to contribute to the general groove is more important and that's what you should focus on when starting out.

Having joined a polish folk band in the meantime definitely helped make this a priority.8

It's slowly coming together. Again, I'm keeping things simple and focusing on simple triads, trying to memorize and make sense of the various inversions and fiddling around until I stumble on something that sounds decent.

Again, knowing how chords are built and what an inversion even is helps a lot. I still have to get the shapes under my fingers and develop an understanding of how they're all laid out on the fretboard, but at least the tidbits I stumble upon make sense.

Allright, time to stop and go woodshed a bit. Rather than a thinking up a coherent conclusion, I'll just throw a crappy picture of this article's main cast instead.

On the left is the old silvertone that I can't play. The one you heard in the sound samples is on the right.

See ya, and happy picking!

-

I'm sure a good setup can help, but I have my doubts it can do wonders. Old instruments don't always age well and sometimes there's just not a lot you can do to bring it back up in shape, short of rebuilding the whole top or some other huge operation which would cost more than the original indtrument..

I'll still look into it, but I'm putting it off for now. ↩

-

The notes that make up each chord. Those come from the scale you just learned, but each chord will be made up of a subset of those seven notes. ↩

-

Although my guitar reflexes tended to land me on the sixth, which I love to overuse. So as long as I know how to resolve it, that mistake can actually sound pretty good. ↩

-

Fourth fret, fourth string, in case you forgot. ↩

-

Again, those are just classic moves I picked up and internalized over the years and that I'm blindly applying to this new tuning. ↩

-

Fifth fret, fourth string. ↩

-

And that's just knowing my way around the fretboard. Being able to transpose my pre-exising guitar technique is a huge boost to get started, but I can feel the wood's not reacting as I expect it to. There's still about a billion things I'll need to adjust to make it sound right. ↩

-

I showed up at the first rehearsal barely able to play the basic bluegrass chop chords. The fiddle player had to show me how to play minor chords, as the chop version of those was too much of a stretch.

I was clearly the beginner in the room, which honestly felt pretty fun. I've struggled quite a bit (still do), but it forced me to take things more seriously, and what little progress I made since then feels all the more gratifying. ↩